by Leon Pantenburg

A great comfort food on a cold night, or in camp after a successful day of fishing is chowder. If you can use some of the catch to make dinner that night, that is an added bonus.

While I fully support and follow catch-and-release philosophies on many species of fish, there are other fish that may need to be harvested to maintain a healthy population.

Always follow local laws, of course, but there are many species of panfish you can harvest, eat and enjoy without guilt.

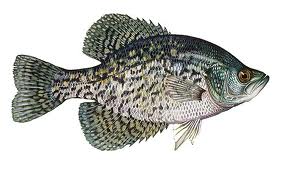

Crappie are a prolific panfish that are available virtually anywhere. I've caught them through the ice, or with a cane pole and crickets on blistering hot Mississippi afternoons.

My favorite crappie rig, is a six-to-seven foot spinning rod, with a small to medium spinning reel. Four-to-six pound line, depending on the conditions, should be about right.

My go-to crappie lure is a 1/16 or 1/8-ounce lead head jig, with a two-inch yellow Mister Twister grub body. Using that combination, I caught crappie all down the Mississippi River. (To view the story of my journey, click on Mississippi River Canoe trip.)

Obviously, variations of color and jig head size abound, but I start out with this combination and usually don't have to do much switching to get into the fish.

The flesh of a crappie is delectable and is a favorite for fish fries. But sometimes, you want some variety, and that's where this chowder recipes comes in. Substitute canned milk for fresh and Half-and-Half, and you can make this recipe on a river bank or in a fishing camp. You could even substitute dehydrated onions, potatoes and corn, and canned butter and make this recipe entirely out of storage foods and fresh fish fillets.

Crappie Chowder

10 crappie fillets (or about 1-1/2 lbs of any firm, white fish. Catfish works very well!)

4 Tbs. unsalted butter

1 small onion, diced

3 medium potatoes, cubed (Yukon Gold or white potatoes are best. They stay firm and don't cook down to mush)

4 c milk

1/2 c. Half-and-Half

1 tsp Old Bay(trademark) seafood seasoning

1 12-oz. can whole kernel corn (fresh sweet corn is best, if available)

salt and pepper

Melt butter in a skillet over medium-high heat. Add onion and sauté until translucent, about four minutes. Remove onions from skillet. Pan-sear crappie fillets for about one minute on each side. Remove fillets from skillet, and cut into small squares.

Add potatoes and onions and cook, stirring frequently for about five minutes or until they begin to soften. Stir in enough cold water to cover potatoes, cover, bring to a boil, add Old Bay seasoning and cook for about 10 minutes. Add fish to potatoes and cook seven minutes on a slow boil. Add milk and Half-and-Half, stir and heat until very hot, but do not allow it to boil. Season with salt and pepper.